About the Australia-Germany Research Network

Australia and Germany have extensive, high-calibre and longstanding research connections that continue to grow. The Australia-Germany Research Network strengthens existing research connections and provides a platform for developing new relationships. It is managed by the Australian Embassy in Berlin and German Embassy in Australia.

Join the AGRN LinkedIn group to receive further updates and connect with AGRN members.

Hear from our AGRN community members

Take a look at the interviews below with members of our AGRN community to hear about their research projects and take on international research collaboration.

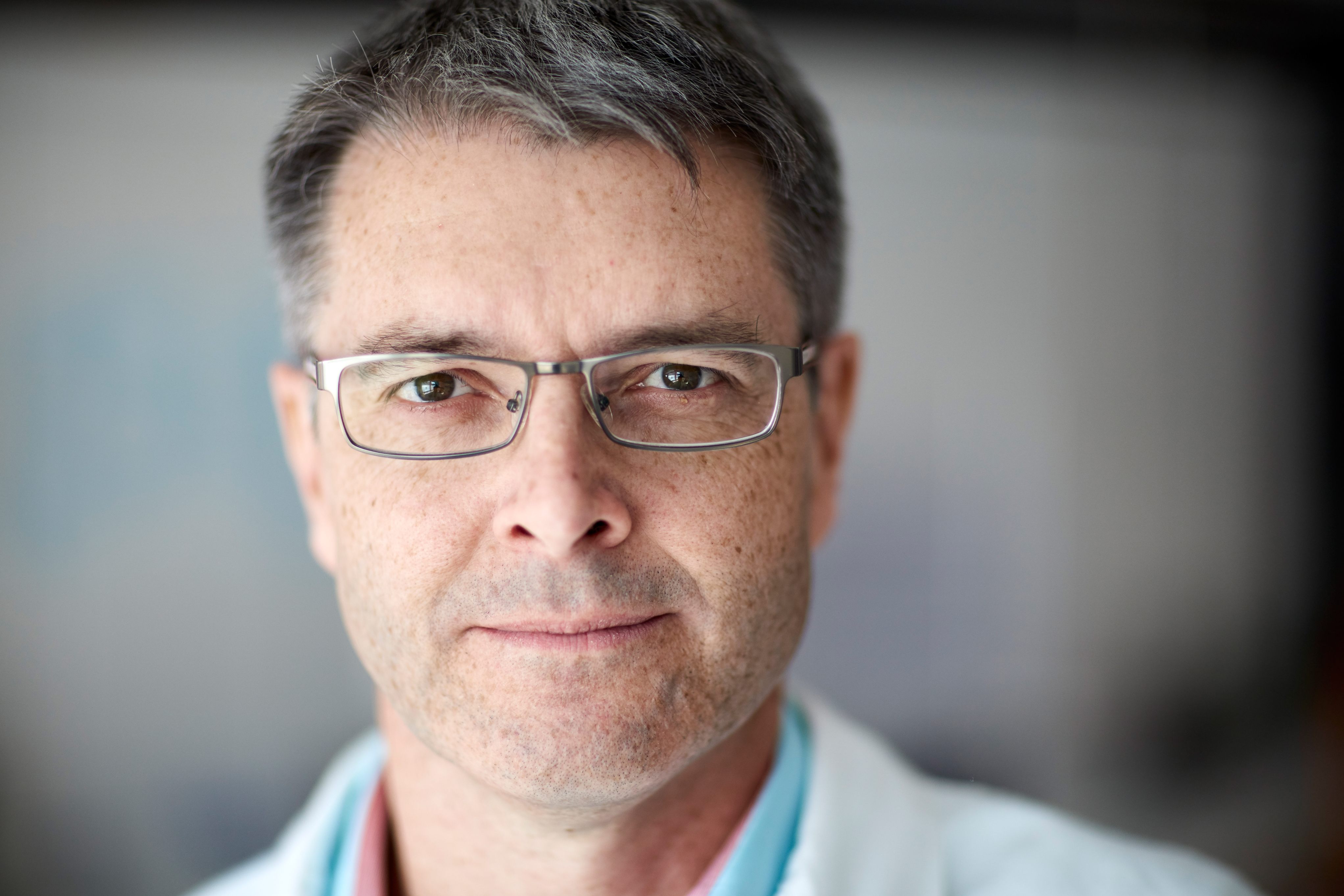

Dr. Enno Aufderheide, Secretary General of the Humboldt Foundation

Dr. Enno Aufderheide has been the Secretary General of the Humboldt Foundation since July 2010. From 2006 to 2010, he was heading the Research Policy and External Relations Department at the Max Planck Society in Munich where he played a key role in the society’s internationalisation strategy. Dr. Aufderheide was a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Colorado in Boulder, USA and is an alumnus of the German National Academic Foundation.

Dr. Enno Aufderheide has been the Secretary General of the Humboldt Foundation since July 2010. From 2006 to 2010, he was heading the Research Policy and External Relations Department at the Max Planck Society in Munich where he played a key role in the society’s internationalisation strategy. Dr. Aufderheide was a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Colorado in Boulder, USA and is an alumnus of the German National Academic Foundation.

In our feature interview, he shares his experience of academic relations between Australian and German researchers and promotes the past 70 years of Australian-German academic collaboration. Since 1953, the Foundation has had the privilege of helping nearly 900 excellent researchers from Australia and Germany to pursue their individual research collaborations.

1. ‘Exzellenz verbindet / be part of a worldwide network’ is the Humboldt Foundation’s key phrase and you have plenty of excellent scientists from around 140 countries in your ranks – 56 of them are Nobel laureates. What skills and qualities make an ‘excellent researcher’ who is Humboldt material?

For researchers all over the world who want to become members of the Humboldt Family, there really is only one thing that counts: their own excellent performance. What it is that constitutes “excellent performance” must always be seen in context. That’s why our selection committees are less interested in ostensibly objective metrics and more in qualitative aspects: Has the person who is applying or has been nominated already demonstrated their ability to implement their own ideas and visibly change their research field? And can it be assumed that they will continue to produce exciting research results in the future, too?

2. More than 30,000 researchers form the tight network that connects ‘Humboldtianer’ worldwide. The Australian Association of von Humboldt Fellows for example meets and celebrates Alexander Humboldt’s birthday annually with dinners across Australia. What makes the Humboldt experience so special and how do you build these connections?

I was very pleased to attend the last dinner held by the Australian Association of von Humboldt Fellows – if only online. Time and again, I am also really impressed by the connecting power of the worldwide Humboldt Family, not least in Australia. The reason the Humboldt Foundation can foster such close bonds with its sponsorship recipients is because we primarily support people, not projects, and because we invest a great deal in individual counselling. Moreover, the Federal President, our head of state, invites the Humboldtians to a reception at his residence during their stay in Germany – a wonderful, shared experience. The Foundation fosters the scientific development of its sponsorship recipients during their entire lifetime, in accordance with our motto: “Once a Humboldtian, always a Humboldtian.” Apart from this, we want our Humboldtians to learn a bit more about our country and people during their stay in Germany, and also connect with one another. So, we invite them to take part in a two-week study tour around Germany, for example. During this trip, lifelong friendships are often forged – and sometimes even more.

3. Alexander von Humboldt never made it to Australia – but since his explorations, numerous German scientists have, and numerous Australians have since also experienced the science and research environment in Germany. In your experience, what are the particular strengths that Australian and German researchers bring to collaborations with one another?

In both countries there are very strong research communities doing excellent research. I think academic relations between Australian and German researchers are founded on great mutual trust. We share values like the freedom of science and confidential handling of data whilst also maintaining transparency in the way we make research knowledge available. This mutual trust is incredibly valuable, especially in times of increasing political tension in the world.

4. The Australian-German diplomatic relationship celebrates its 70th anniversary this year and research and innovation has played an integral part in our partnership. Which scientific collaborations in recent years have you found particularly formative?

Seventy years of Australian-German diplomatic relations also means almost 70 years of the Humboldt Foundation promoting Australian-German academic collaborations, because next year, we will also celebrate our 70th anniversary. Since 1953, the Foundation has had the privilege of helping nearly 900 excellent researchers from Australia and Germany to pursue their individual research collaborations. The first Australian fellow came to the Theological Faculty at the University of Göttingen in 1955. And later, for instance, Australian fellows conducted research together with Reinhard Genzel and Klaus Hasselmann who both won Nobel Prizes in Physics in 2020 and 2021 respectively. All the collaborations we supported helped to advance research and build trust. Many have spawned long-term contacts, which in turn have generated further institutional linkages. Cooperation between individuals has thus had a structural impact on academic relations between Australia and Germany. Today, I am very pleased to note that this momentum continues unabated and that new generations of researchers are also grasping the opportunity to work together.

5. With the COVID-19 pandemic impacting international research exchange for the third consecutive year, where do you see international collaboration (and Australian-German in particular) heading?

In 2020 and 2021, the Humboldt Foundation did indeed experience a slight drop in the number of applications and sponsorship figures for Australian researchers. This was obviously a result of the pandemic and travel restrictions. Some collaborations could be continued or launched online; some researchers tried out new forms of distance cooperation. This experience will inform the way we design scientific cooperation between our countries in the future, too, and perhaps be quite helpful in overcoming the physical distance. But even so, personal encounters and immersing oneself in new scientific and cultural environments are still indispensable for creative thought processes and sustainable personal contacts. I am convinced of this. Now, as the situation is gradually improving somewhat, we are delighted to see that increasing numbers of Australian researchers are coming to Germany. I am confident that this trend will continue because there is enormous potential in Australian-German scientific relations – and not only in large-scale energy and climate projects but also, and especially, in smaller projects that, thanks to the spirit of scientific discovery, break new ground.

Dr. Bradley Ladewig, Group Leader Photochemistry (PHO) at Karlsruhe Institute for Technology, Germany

Dr. Bradley Ladewig is the group leader Photochemistry at the Institute for Micro Process Engineering at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Examining the decarbonization of chemical manufacturing processes and exploring engineering technologies for hydrogen, Dr. Ladewig is one of the key scientists finding the solutions we need for a successful energy transition. In our feature interview, he shares insights into his work with us, his hopes for a greener future and his unique international experiences - his research in has lead him all over the world. Learn more below!

Dr. Bradley Ladewig is the group leader Photochemistry at the Institute for Micro Process Engineering at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Examining the decarbonization of chemical manufacturing processes and exploring engineering technologies for hydrogen, Dr. Ladewig is one of the key scientists finding the solutions we need for a successful energy transition. In our feature interview, he shares insights into his work with us, his hopes for a greener future and his unique international experiences - his research in has lead him all over the world. Learn more below!

1. Can you tell us about your research and your current focus?

My focus is entirely on the energy transition in Germany and finding new materials, technologies and solutions that will help us achieve our target of zero net emissions in 2050. Germany has several important industry sectors like chemical manufacturing which pose really interesting challenges for decarbonization, and part of my current research focus is on developing new materials to help achieve this – for example finding new catalysts for electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to useful and valuable chemicals. Another element of my work is on chemical engineering technologies for producing, storing and transporting green hydrogen – since for many countries (including Germany and Australia) hydrogen will be a crucial energy carrier.

2. You completed your higher education and PhD at Monash University and the University of Queensland in Australia and are now working at one of the leading German research institutes. How have you experienced the research environments in both countries?

International experience is one of the reasons I love my career. I was a student in The University of Queensland, an exchange student at Nottingham University, then conducted part of my PhD research at Imperial College London (with a Chevening Scholarship). I was a postdoctoral researcher with the CNRS in France, did some further postgraduate study in education at Monash University while working there, then had several years working at Imperial College London, before moving to KIT Karlsruhe (with support from the Alexander von Humbolt Foundation).

The research environment is all these places is the same, everyone is striving to do excellent research to solve important problems – what is different is the culture. How people relate to each other, the way of communicating and collaborating, whether colleagues socialize outside of work, and of course the language – these things make the experiences different and enriching.

3. What has your extensive research collaboration experience taught you about what German and Australian researchers learn from each other?

I find German and Australian research collaborations to be enjoyable and productive. From a personal perspective, both working cultures are fairly direct, honest and straightforward with a focus on solving problems. Germany has a proud reputation of industrial export-oriented success and at least in my field (engineering sciences) there is a focus on partnering with industry and delivering talent (i.e. our graduates) and solutions (materials, technologies) that meet the needs of industry. KIT Karlsruhe has some amazing alumni, including Fritz Haber – awarded the Nobel Prize in 1918 for invention of the Haber-Bosch process for making ammonia. In a beautifully circular way, ammonia is currently being explored as a hydrogen carrier and could form the backbone of a global green hydrogen supply chain, including from Australia to Germany.

Overall I strongly support all options for the exchange of students and staff between Australia and Germany. In my experience, the best collaborations are those where participants genuinely understand and appreciate the cultural background of their counterparts.

4. What role do you see your research playing in helping the world achieve a greener future?

Our research is entirely focused on achieving sustainable solutions to the major global challenges in energy and environment. We literally don’t do anything else! If I end my career and can point to some material or technology being used industrially, whether for green hydrogen or CO2 conversion or something else I haven’t even started work on yet, then I will be satisfied. I also place great emphasis on education – our graduates will work in companies that actually realize the energy transition, that develop the technologies, services, products that people need. The impact I have on the thousands of students I teach over my career can have a ripple effect, spreading far and wide in many different sectors, so I really make a big effort to do that part of my job well. Maybe my biggest contribution to a greener future is through people instead of products and publications!

5. In your view, how can research institutions such as the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology get involved in ongoing public debate about lowering emissions and creating a sustainable future?

Here the answer is really clear, KIT is already doing this extremely well. We have really extensive outreach at every level, from local school students to our Professors contributing to the highest level discussions in the Leopoldina, and everything in between. For example, KIT Science Week runs from 5-10 October 2021 on the topic of “The Human in the Centre of Learning Systems” and includes keynote speeches, TED talks, panel discussions, an exhibition, a citizens dialogue platform and campus tours, all the bring the public into our research and education and to engage with them.

In a time when there are some elements of society not fully engaged with science-led expert opinion, it has never been more important that researchers and research institutions really listen to members of the public, to hear their questions and concerns, and answer them clearly and honestly. Major events like KIT Science Week are one way to do this, but we also need to do it everywhere, all the time, when talking to family, friends, neighbors, young people and old – everyone.

6. What is the defining feature of science and education in Germany, from your perspective?

Germany has a clear understanding, both at a political level and within the wider public, that society benefits from investment in education. I am so proud to live and work in Germany and see that all kinds of research is funded from the arts, humanities, medicine, natural sciences and engineering.

Prof. Dr. Thomas Scheibel is professor for Biomaterials and Head of the Department at the University of Bayreuth, Germany. Through his research and in his role as Vice President for Internationalisation, Gender Equality and Diversity at the university, he has built a strong network with Australian universities including leading institutions in Melbourne.

In our feature interview, he shares his experiences of opening a gateway office in Melbourne and establishing a joint PhD programme, and how his fascinating research about spider silk promises to solve one of the biggest challenges of our time: reducing the plastic waste problem and environmental burden of common crude-oil derived products.

1. Can you tell us about your research at the Fiberlab and what powers spider silk holds?

Spiders have evolved silks which uniquely combine tensile strength and extensibility, making it the toughest natural fiber material on earth, and even surpassing man-made materials such as polyamides, polyaramids or other performance fibers. In contrast to those plastic fibers, spider silk is a green polymer consisting to almost 100% of proteins, which are fully biodegradable. Therefore, the benefits of spider silks are manifold. Major drawback in the past has been the low producibility partly based on the cannibalism of most spiders, which made a natural scale-up production using spiders not feasible.

A breakthrough was the establishment of a scalable biotechnological process enabling the production of recombinant spider silk proteins by our group in 2004. The biotech process enabled for the first time the scale up of the production of such proteins at constant high quality and yield. The innovative technology developed in our group brought new products to the markets (e.g. cosmetics, textiles, etc.) which – apart from the outstanding properties of the material – might pose a solution for one of the biggest challenges of our time: reducing the plastic waste problem and environmental burden of common crude-oil derived products via sustainable and biodegradable performance biogenic materials.

2. How did your research connection with Australia develop?

My first contact with research in Australia was back in 1995 during my PhD, where I visited a collaboration partner in the field of my PhD topic on heat shock proteins at the University of Sydney. Shortly after starting my own group in 2001 working on spider silk, we initiated a research collaboration with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) on recombinant structural protein production and processing, which has lasted ever since.

Upon getting funding from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for a Bayreuth-Melbourne research network, we intensified collaborations with several Australian researchers from 2015 on. The focus of the Bayreuth-Melbourne Polymer-Colloid network, which I am heading as the chairman, is the development of innovative materials for advanced energy as well as medical applications. Initiated in Bayreuth, the network combines leading research groups in polymer and colloid science. The Australian partners of the network are mainly located in the Melbourne area, such as The University of Melbourne, Monash University, Swinbourne University as well as CSIRO. We further initiated a double PhD program in that area with all three mentioned Universities, and continuously expand our research activities in the named two areas.

3. You have been integral to the opening of the University of Bayreuth’s gateway office in Melbourne. Why Melbourne, and what has the process of opening the office been like?

After my election as vice president for internationalisation, gender equality and diversity at the University of Bayreuth in 2016, I started to focus the University’s internationalisation strategy. One part therein was the implementation of gateway offices in a few strategically important regions world-wide. The first gateway office was launched in Shanghai, China in 2016, the second one in Melbourne in 2018 and the latest in Bordeaux, France in 2020.

For years there have been strong research collaboration between the University of Bayreuth and several Australian Universities, with a focus on Melbourne. However, there are also close collaborations with Sydney, Newcastle, Brisbane, Sunshine Coast and Perth. One focus ever since has been the mobility exchange of students and researchers. Based on the latter one, strong research collaborations have also evolved. Beyond Energy Science and Biomedicine, the collaborations encompass sport science, law and business schools, environmental sciences and material sciences. To intensify the existing collaborations, we started a gateway office in Melbourne, where we had the most collaborations. The office is entitled to support all researchers and students throughout Australia concerning study issues, visa, house-hunting, search for internships and many more. And this support is going also the other way around for students and researchers from Bayreuth to Australia.

4. COVID-19 has made international scientific exchange more challenging. How has the pandemic impacted you and your students’ work? How is it affecting universities’ international strategies?

Strategically, COVID-19 did not influence our activities or decisions concerning collaborating with down under. On a daily basis there have, however, been drawbacks – a lot of cancelled research visits, cancelled conferences and strategic meetings (although they have been substituted partly with online video meetings, meetings in person make such a huge difference…).

Especially our PhD students have had impact on their research, and we have launched a press release concerning this issue beginning of January 2021, in which two phd students share their experiences.

Bronwyn Fox is the founding Director of Swinburne University's Manufacturing Futures Research Institute where her mission is to support transition of Australia's industries into Industry 4.0.

1. What has been the nature of your work with institutions and industry in Germany?

Swinburne has a range of German organisations that we cooperate with. These include the University of Stuttgart and its industry on campus model for research, ARENA 2036, the University of Applied Sciences Ravensburg-Weingarten, the University of Bayreuth, the Fraunhofer (in different locations), Siemens, Daimler and other industry partners. Our engagement has been broad in all areas relevant to product design and development, engineering, advanced manufacturing (planning), material sciences, specifically for composites, and a range of technologies around Industry 4.0.

We have had many research and industry practitioners visit us here at Swinburne, and Swinburne staff go to Germany to work with our partners there. We work collaboratively on joint research projects, actively exchanging data, ideas and people. For instance, we just had three students from Stuttgart working at Swinburne on their graduation projects and, in turn, one of our PhD candidates just finished an exchange with Stuttgart and Ravensburg-Weingarten working in the labs over there.

It is such a fruitful collaboration with our German partners in every way. We benefit from technological expertise in Germany, while we have a range of diverse use cases and projects to offer that we all benefit from. The highlight is undoubtedly the knowledge exchange and our deep conversations about emerging technology and trends are invaluable.

2. How do you think we can best navigate the transitions Industry 4.0 requires in a way that harnesses the opportunities, while addressing growing anxieties regarding the disruptive nature of automation?

I recently had the privilege of chairing an expert working group on an ACOLA Horizon Scanning report on the Internet of Things (IoT) which will soon be launched through the office of the Chief Scientist. This report examines the impact the IoT is likely to exert on Australia over the coming decade. Many of our partners in Germany contributed to the report and I would encourage everyone to read it as it outlines both the challenges and opportunities of digitalisation and there are many, many opportunities.

Industry 4.0 incapsulates the effects that digitalisation and IoT have on design, engineering and manufacturing. We will see new types of jobs emerge with this and new skillsets being required to support these jobs. There is uncertainty around what this means to organisations and people, which is why it will become so important to proactively work with industry on upskilling, the transforming of labour and exploring the new opportunities Industry 4.0 presents for all stakeholders.

At Swinburne we have already introduced several training and education programs around Industry 4.0 and we expect the demand for these to grow rapidly in the near future. People and organisations who embrace the opportunity to transform themselves actively and early are likely to lead in this new environment. However industry, particularly SMEs are nervous about exploring new technologies with so many products and limited knowledge making this a potentially risky and costly exercise. Swinburne works closely with industry to enhance understanding of new technologies, products, services and new business models made possible by Industry 4.0. We also have a number of open Testlab environments where industry can come and explore how Industry 4.0 technologies work and better understand what might enhance their business, prior to investing.

3. What do you see is the potential value to Australia in investing in advanced manufacturing and the production of composite products?

For Australia, Industry 4.0 offers huge potential to regain strength and momentum through sovereign manufacturing: creating high quality products, but also new types of services, at a competitive cost. Digitalisation will facilitate lean, high quality production, knowledge-based decision making and flexible collaboration with others around the world to access global supply chains.

Specifically around composites, there are huge opportunities to make production more efficient, cost-effective and of better, replicable quality. This is also immensely relevant for automotive, aerospace and other transport industries where these qualities are important but also where light-weighting without decreasing strength is also paramount. Here light-weight composites allow increased performance but will likely also drive implantation and utilisation of new energy sources such as hydrogen.

To this end, we have a global program of work that will utilise our joint facility with CSIRO, the Industry 4.0 Testlab for Composite Additive Manufacturing which will be operational early next year. We have a global program of work to work with industry to utilise the facility funded through the Australian Federal Government and the Global Innovation Linkages Program and the “InterSpiN” program through the BMBF in Germany where the projects are led by ARENA2036.

4. What are your future plans and goals for continuing this collaborative research project, and has this been impacted by COVID-19?

Of course, with international travel being reduced so drastically at the moment, there is currently less opportunity for the physical exchange of people. However, we have built mutual trust through many visits over the past four years and this has set us up well to continue our work digitally. We are very much looking to getting back to seeing each other “unvervirrt”.

We really want to grow our engagement with our German partners. We are already looking at new project ideas and opportunities to collaborate in different areas. COVID-19 has not slowed down our ambitions in any way. If anything, it has facilitated our drive into a more digital world and forced us to find work-arounds to any perceived barriers that may present themselves.

As we have been building the Testlab, we always promised to push the boundaries of virtual commissioning. COVID-19 has forced us to accelerate this, quite literally as with the support of our partners in Germany we conducted virtual factory acceptance tests in June and will now use digital tools to support the installation and commissioning of the equipment in the next few months.

5. In your experience, what are the particular strengths that Australian and German researchers bring to collaborations with one another?

Our German partners bring immense expertise and a deep, deep understanding of technologies to the table. It is such an incredible wealth of knowledge and technological know-how. I’m always grateful for their openness and generosity in sharing ideas. In Australia we have strength in thinking laterally: this means we often simply do not see the barriers that others see which leads us to explore interesting and novel ways of applying technology and doing things in new ways. This is really where I think we match extremely well, in the translation of the extraordinary technical abilities to novel use cases and applications.

Prof. Dr. Joybrato Mukherjee, President German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)

(Interview AGRN Newsletter October 2019)

Currently, Prof. Dr. Joybrato Mukherjee is Vice President of the world's largest organisation for academic exchange, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and in January 2020, he will become its President. In his role at DAAD, Professor Mukherjee drives a wealth of opportunities for students and researchers to conduct invaluable international research projects and collaborations in Germany and Australia.

In this interview, Professor Mukherjee delves deeper into Australia and Germany's excellent research relations, and explains how bilateral exchange in Tim Tams could further ensure future prosperity of this successful collaboration.

1. As of 2020, you will be serving as the President of the DAAD, having performed in your current role of Vice President since 2012. What do you see as the major benefits of DAAD’s aim to promote international exchange for students and researchers?

The DAAD has the motto ‘change by exchange’, which works on several levels: It works on an individual level with students and scholars gaining personally from study abroad experiences and research collaborations with international partners. It also works on an institutional level with international collaboration being at the heart of the strategic development of universities. ‘Change by exchange’ further works on a global level with close relations on a university level forming an important part of international relations between nations. Individually, institutionally and as nations, we depend on the exchange of ideas and collaboration – particularly when it comes to the major

challenges of our time, which can only be addressed jointly across nations on a global level. The DAAD represents the world´s largest funding organisation for the international exchange of students and researchers: In 2018, DAAD funded 145,188 people, thereof 63,680 foreigners and 81,508 Germans. It is thus a forerunner of large-scale international collaboration to the benefit of both Germany and its partner countries.

2. You recently visited Australia in your capacity as Vice President of DAAD and President of JLU Giessen. What Australia-Germany research collaborations did you learn about?

I learned of the large scope and great variety of Australian-German research collaboration: By way of more than 600 institutional agreements, 181 German universities cooperate with 49 Australian universities. In 2018, DAAD and Universities Australia funded 132 projects through the “Joint Research Co-Operation Scheme”. In addition, there is a long tradition of Australian-German research collaboration in individual cases, such as this year’s celebration of the 20th partnership anniversary between Justus Liebig University (JLU) and Macquarie University. Alongside Monash University, Macquarie University belongs to JLU’s most important strategic partner universities worldwide. A few success stories reflect the prosperous partnership: Already in 2012, the first German-Australian International Research Training Group (IRTG) in reproductive medicine funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) was established between Monash University and JLU. In 2019, a JLU representative office (“JLU Information Point”) has just opened at Macquarie University. Despite the huge differences between the higher education systems of Australia and Germany, Australian and German universities are natural allies when it comes to collaborative research at the highest level.

3. How will the new DAAD-Ortswissenschaftler-AGRN Research Ambassadors initiative, launched by DAAD and the German Embassy in Canberra, further promote bilateral research cooperation?

The new DAAD-Ortswissenschaftler and AGRN Research Ambassadors have a very important mission. As experts of both the Australian and the German higher education system, they serve as bridgeheads between German and Australian universities. I personally attended their latest preparatory meeting in September in Sydney and was able to see for myself that the members of these two programmes are perfectly equipped to support German and Australian researchers. They promote bilateral research cooperation based on their expertise in three main areas: their deep knowledge of the characteristics of both higher education systems, their insight into funding

programmes provided by DAAD, DFG and other funding agencies as well as their personal experience as researchers at German and Australian universities.

4. What role do you see digitalisation playing in the future of the Australia-Germany research relationship? Do you expect it will broaden existing links? What opportunities does digitalisation offer research collaboration in the social sciences?

Digital tools and methods can help to bridge the geographical distance between collaborating partners located in Australia, Germany or anywhere else in the world. The ever-growing importance of digitalisation in higher education opens up opportunities for collaboration. Through various ways of sharing data and making knowledge more easily accessible, digitalisation facilitates communication and joint research and teaching. JLU and Macquarie University are implementing co-teaching Master classes in the social sciences, for example. On a global scale, digitalisation is a key issue for the future of environmentally friendly collaboration in higher education.

5. What are the key similarities and differences between the Australian and German research landscapes? In what ways do these characteristics complement each other?

One of the main differences that sets Australia apart from Germany is the research funding landscape. Teaching and research at the highest level combined with commitment to society, however, are shared by both Australian and German research. Both landscapes acknowledge the importance of international networks to face global challenges to the effect that these similarities complement existing differences.

6. Was there anything that you really fell in love with in Australia that you brought back to Germany in your suitcase? Did you come across anything in Australia that could be shared with Germany and thereby benefit both countries (eg. public transport, cuisine etc.)?

Improving the special link between Germany and Australia, in terms of learning from each other, certainly regards the chocolate branch. I always take Tim Tams with me on my way back from Australia!